Interview

Public and Private Space

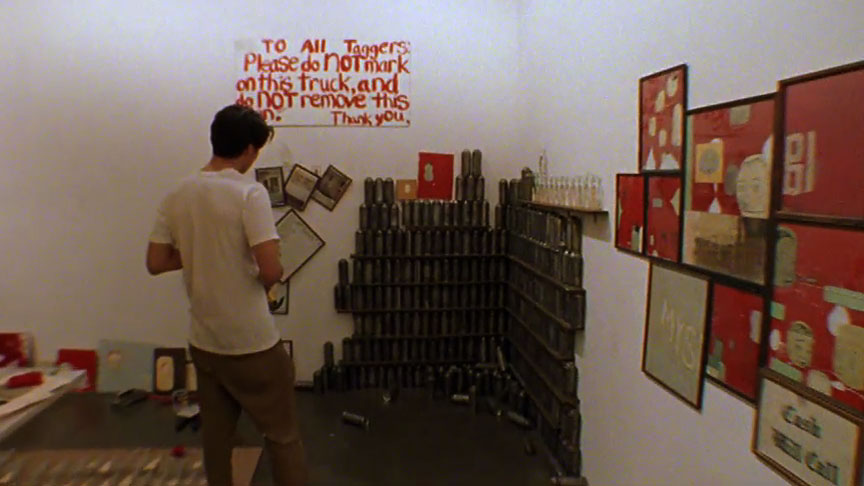

Barry McGee installing work at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 2000. Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 1 episode, "Place," 2001. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Barry McGee talks about his interest in the history of graffiti, and how he approaches installing his graffiti-style paintings in a gallery space.

ART21: You seem to be very interested in the history of graffiti, as something that’s been happening since ancient times.

MCGEE: Of course, if I see something, I know it’s something that everyone does and have done for centuries upon centuries. The thing that I’m interested in now is the idea of getting rid of it—this war on getting rid of it, and this idea of silencing it or trying to get rid of something. To me, that’s the more interesting thing: how, in today’s climate, there can be huge billboards and bus-stop kiosks with advertising, and then along comes, like, a simple tag or something that someone does on it, and that thing is immediately removed overnight. To me, that’s what is really interesting about the whole thing now. It’s about the idea of public space and how people can function in public space anywhere.

It’s gotten tighter and tighter, since the Reagan-Bush era—the idea of private space and who can go into this space or a park (what is considered a park, now). As those things get tighter and tighter, and privately owned property and surveillance and whatnot is increased, so is this thing on the street. It also increases, too, for some odd reason. And I’m not exactly sure why it’s that way. But I find it really interesting how quickly they want to get rid of this thing. There could be a rooftop that is just sitting dormant for a while, and someone goes up there and does an amazing piece of graffiti or whatever you want to call it. And then that’s removed, and two months later, there’s a huge billboard over the whole spot anyway.

So, it has to do with money and who has access to space. And when I feel like the access to space is cut off for the general public, I feel like that makes me want to do stuff on the street, even that much more. And the stuff in the galleries is just arty. The art crowd is arty, and it’s the same people. Sometimes I feel like if I do something indoors, my circle of people that sees things is getting smaller and smaller—where if I’m outdoors, it’s open to anyone to look at, or see or hate or whatnot. But doing stuff indoors—there are some good things about it, but I know the audience is very limited.

ART21: But isn’t painting an installation in a gallery like taking over that space, opening it up to possibly new audiences?

MCGEE: Well, yeah, it’s like that, and it’s even like that in rundown and abandoned areas. It’s what I know me and a lot of friends just consider ours, you know? It’s really hard to have a feeling of ownership in today’s climate, too. I think the idea of owning something, or a space that you can use or whatnot—I’m very cynical of it. And the idea of private property—someone putting up a fence around something, a chain-link fence, and posting “Private Property” signs—I have issues with those type of boundaries.

Barry McGee installing work at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 2000. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 1 episode, “Place,” 2001. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: But at the same time you seem very protective when it comes to an idea of mental space, like all the advertising messages on billboards that get crammed in the brain.

MCGEE: There’s a lot of talk of how damaging graffiti is and the destruction that happens with graffiti, but there’s actually no damage. It all can be removed or painted over with a roller. So, there’s the media’s idea of damage and destruction, this [idea] that’s slightly askew. To me, if there are commercial jingles from the ’70s or ’80s that I remember and that are stuck in my head, that’s damage to me. Like, you’re driving down the street and all of a sudden you’re humming along to some commercial that you remember when you were a kid—to me, that’s far more damaging. The billboards are very subversive, and advertising is very subversive, whereas most of the stuff that’s done on the street is very close to the truth. There’s not so much subversion involved.

ART21: So, would you say that street stuff tends to be unmediated, closer to a person-to-person interaction?

MCGEE: It’s person-to-person. A lot of it’s a very simple form of communication, but it’s very direct, also. If someone feels strongly about something, it’s just a matter of going out on the street and writing what you want, and there it is for you. It’s out there immediately for the people to have to deal with. And it’s just like a headline on a newspaper—or a billboard that shows up in your neighborhood overnight, and you’re just, like, “Oh, new Sprite ad” or “A new Mountain Dew ad.” And to me, it’s all kind of fair game out there. But one seems to keep getting removed constantly, and one just keeps on building and building in neighborhoods and on the sides of buildings. And (as I’m sure you know, in Manhattan), it takes over whole entire blocks of buildings. So, there’s no mystery; I know why it exists. There are people that have a lot of money, and there are people that have next to nothing. But it competes with the space that people consider the public space.

Barry McGee installing work at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 2000. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 1 episode, “Place,” 2001. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: Were you conscious of graffiti as a kid, as something that competed against advertising?

MCGEE: I knew it existed, but I think I was really always very comfortable. When someone introduced it to me, I’d seen graffiti around, but I never had an idea of what it was. But as soon as I got more and more involved with it, it seemed like freedom to me. It was very empowering, and it is something I enjoyed doing a lot, and the people that were doing it were very interesting to me, too.

ART21: Were there any people who were major influences for you when you began doing graffiti, any master teachers?

MCGEE: There were some strong influences for sure, some very strong influences. I started in ’84, and that’s in the Reagan era. There was a lot of protesting, and there was a lot of interesting music going on at that same time. So, a lot of those things had big influences on me—as far as punk rock and hardcore music and just people doing things on their own—all these things that were going on. People seemed like they were definitely more active then—had an opinion about things. Whereas now, I think people are, like, “I got to get mine before . . .” you know? It’s more cutthroat now. I think I’m a bit more cynical now. I think people were a lot more politically aware. There was a lot of the ACT UP and other groups of people that were constantly wheat-pasting on the street, and there was a lot of protesting and a lot of questioning of things. But I think, going into the mid-’90s, it all kind of changed. And there was a big shift.