Interview

Spirituality, Chaos, and “Inopportune”

Cai Guo-Qiang. Tigers with Arrows, detail, 2005. Gunpowder on paper, mounted on wood as nine-panel screen; 230 x 692 cm (90 9/16 x 272 7/16 in.) overall. Installation view at Cai Guo-Qiang's studio, New York, NY, 2005. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power, 2005. Artwork courtesy of the artist. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2005.

Artist Cai Guo-Qiang discusses the inspiration for his work, his methodology, and his 2004 installation series, Inopportune.

ART21: Can you talk about the El Greco poster that’s hanging in your studio? Are his paintings an influence on your work?

CAI: Cultural exchange is very important. People are always asking, “What is it you’re interested in art, historically? Who has influenced you the most in art history?” These are repeated questions that I have had to think about and kind of crystallize these ideas—who’s important and why?

I’ve always, in my heart and spiritually, felt this affinity towards El Greco. During the Renaissance, dissecting a scene, having proper perspective was revered. But for El Greco, he saw beyond that already; he saw that these were only devices. His work has pride, spirituality, and his own compromises as well. What he has tried to express was beyond what these rational artists were doing at the time. This spirituality is what attracts me the most. This conversation is exchanged with the unseen forces and with the spiritual world.

We are working in an art that’s called “visual art.” And by definition we are visually driven. In a way, we are bound by that, limited by this very fact. So, it’s easy for us to depict things of this physical world, of the way we live now, but it’s very difficult to depict things that are not seen but have a profound effect on us. It’s very difficult to show life beyond death, life beyond this life. But there is something that he understood that these other Renaissance artists were depicting. Of course, a lot of this is religious imagery that is meant to evoke something that’s eternal, that’s very spiritual. But he knew that these were only subject matters, not necessarily what the works were representing in essence. While the subject matter is about spirituality, they were using man as a manifestation of that. So, it was very much based on man. Maybe El Greco inherited something of the past beyond the Renaissance.

ART21: Is that an analogy for your work as well?

CAI: Yes, it could be said as such. However, I live in a different time from El Greco. Our methodology and style are different. The way we approach art is different, so the representation may be different. Even though in thought, in spirituality, or in philosophy, there are some links, our form is different.

I come from a background of alchemy and Taoism, and I’ve combined that with modern physics and a modern worldview. I know, for example, space could be totally engaged in a type of work that envelops the audience. The work could play out in time; there could be a time element in there. These issues broaden our representation, our way of working. They represent our time as well.

Cai Guo-Qiang at work on Tigers with Arrows (2005) at Fireworks by Grucci, Brookhaven, NY, 2005. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: Can you talk about your working method a little more, your methodology?

CAI: It’s very difficult to articulate exactly what that methodology is—even for myself. If I knew it all and understood it all, if I could clearly say it, then it would become a product on a shelf.

It’s something I’m continuously exploring and trying to form. There are perhaps two ways of looking at that. One is a methodology in how you view the world, how you see and understand the world. I take a lot from the ancient philosophies, from Taoism. And then there is another side: how you specifically approach art or life, exactly how you live in this world, how you make art. One is more conceptual while the other is more practical. I also employ the basic philosophies of medicine—Chinese medicine or feng shui. These are very much infused in the more daily living and the art making process.

I can be a little bit more specific about some of these ideas that I live by. For example, movement cultivates vitality. This is the idea of living within the chaos of time and space. Maybe not everything has to be resolved with a finite answer. Rather, sometimes you can allow uncertainties to exist within the same space and situation. These are obviously ancient ideas from China. Because I’m Chinese, this is what I know. Some of these ideas are also found in the Western frame of mind as well, maybe in a slightly different perspective, but the principles are there. Perhaps during the Age of Reason, Enlightenment, and Industrial Revolution, some of these ideas were cast aside for more concrete analytical ways of approaching life. But since then, in postmodernism, some of these ideas have resurfaced, even in science. So, the chaos theory—it’s technical—in Chinese, it translates as either “murky mathematics” or “chaos mathematics.” In astrophysics and math, these are ideas that are employed by the most modern thinkers as well. I come from this perspective.

ART21: How does one work with chaos as a material for art—for example, fireworks and gunpowder?

CAI: With time, you start to get to know the material. You actually develop a way to know how it will behave, to a certain degree. First, you have to accept that it’s uncontrollable and that there is an accidental element. You have to accept it and then work with it. I’ve worked with the material for so long that I’ve gained an understanding of how it works. Sometimes I can control it better than I realize, better than I expect. Then at that point it becomes stagnant. So, it’s very important that there is always this uncontrollability that’s a part of the work. My way of doing it is just to flow with the material, go with the material, and let it take me where it wants me to go. So, I continuously want it to give me problems and obstacles to overcome.

Cai Guo-Qiang at work on Tigers with Arrows (2005) at Fireworks by Grucci, Brookhaven, NY, 2005. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: What sort of obstacles?

CAI: If you follow that train of thought, it might get a little boring, so let me use another example. This whole process of making drawings is very much like lovemaking. From the very beginning, of laying down the paper, it’s like laying down the sheets on the bed. First you lay down the sheets, and you have this idea of what you might want to do today, in form or in action—what you would like to accomplish. Then you bring in the materials, you lay them out, apply pressure here, but not too much pressure here. You know what kind of effect it might have. How much attention you should give to a certain area, how much material you should use, and how you should play off another balance are all things that you have to consider throughout.

It’s a very long process. You keep going at it and always working towards a final goal. But it’s a very prolonged process, and all the time there’s this feeling that you just want it to explode, to finish. There’s continuous control of pressure: you want to set this on fire, to explode it, but yet you are afraid that maybe it’s too early, maybe it’s not the best time yet, maybe you need to work on it a little more.

The explosion process obviously could be equated to the climax. Immediately afterwards, we’re trying to clean it up, put out the flames, put out the sparks, clean up the pieces, clear it away, so you can see the work. Afterwards you have either great satisfaction or you have disappointment as to your entire performance. These play back and forth: the material, your idea, and what you’re working on. It’s actually quite a biological process; it’s very visceral.

If we equate making artwork with making love you can see a different approach here. You can talk all day about philosophy: ancient philosophies, modern philosophies, art history, criticism, theories. You can talk about subject matter, context, historical context, the contemporary, postmodernism. You can talk about form and representation. All these things can be discussed, but in the end, it’s really how you do with this given situation. You can have all these ideas about lovemaking, but it’s really the culmination of all these things. It’s your physicality there, how you’re involved in that moment.

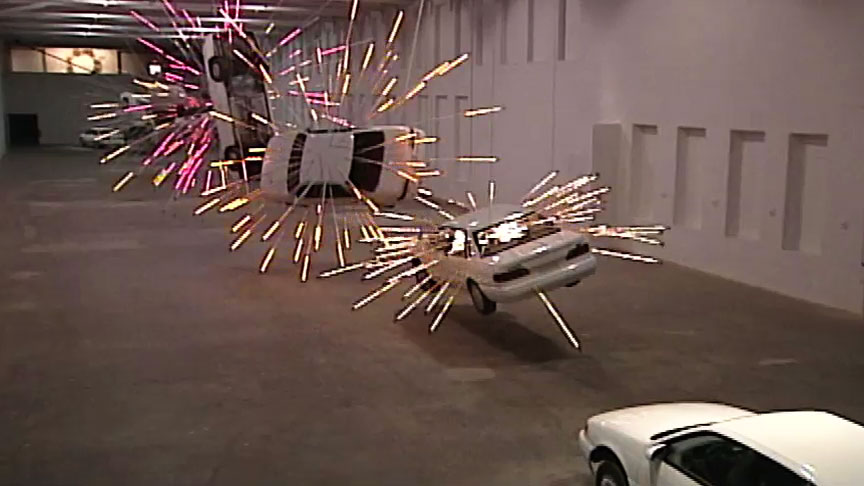

Cai Guo-Qiang. Inopportune: Stage One, 2004. Cars, sequenced multi-channel light tubes; dimensions variable. Installation view at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, 2005. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. Artwork courtesy of the artist. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: Can you discuss the title of the piece, Inopportune, at MASS MoCA?

CAI: Ever since September 11th, the idea of terrorism is always on our minds. It’s ever so present. And while car explosions have been around for a long time, they have a heightened sense of reality in our minds. Inopportune obviously has a direct reference to these conditions that we live in now. But making an installation that is so beautiful and mesmerizing that also borrows the image of the car bomb already has inappropriateness in it. Of course, there’s a concept behind it, but never mind the concept—just the very fact is a difficult thing to overcome. It’s difficult to resolve for some people. Whatever it is, it’s a quite direct reference and commentary about some of these issues. So, maybe in this way, it’s kind of unfashionable or inappropriate, or inopportune.

Since the ’80s, maybe the ’90s, irony is such an important part of work now. There’s less direct commentary or direct reference to certain social problems or phenomena in our world. Nowadays, artists tend to stay away from these kinds of ideas and take a more humorous approach, poking fun at society. All of my work is quite direct—for instance, the car bombs or the tigers. It’s a quite direct reference and commentary about some of these issues.

Cai Guo-Qiang. Illusion, 2004. Three-channel video installation: DVD projectors, 3 DVD players, 6 × 24-foot screen, car, spent fireworks. Installation view at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, 2005. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. Artwork courtesy of the artist. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: In Inopportune, both the cars and the video installation loop, either metaphorically or literally. Can you talk about the notion of circularity in these works?

CAI: Just like the cars in the main gallery—as the first one takes off into the air, tumbling in a very dreamlike fashion, it lands back on its four wheels, safely, undamaged, unharmed. It repeats, going right back to the very first car again, suggesting that it’s just one car. And like the video in Times Square—it happens, yet it looks right back into itself and it plays out again. This continuous loop suggests that something might or might not have happened—this illusion that we are seeing in front of us. The drawing may just clarify it or crystallize this idea to actually put it in a more physical form of the circular shape.

ART21: How did you plan the work? How is it sited?

CAI: When I first saw the exhibition space—that elongated space, one hundred meters long and eighteen meters wide, for the work that became Inopportune—I felt that it was like a section of an avenue, a road that had been transported there with that concrete floor. The idea of doing a project having to do with car explosions had been on our minds for some time. But these kinds of conditions that are presented to you bring forward concrete ideas, so it seemed like a really perfect opportunity to show this idea. And of course the physical manifestation was also inspired by the space itself.

And then while we were looking at how to lay out the entire exhibition, it wasn’t just an avenue I was given—it was like a landscape. You travel upstairs, you come back down again, and then you go up these ramps or go into the adjacent space. I wanted to further that idea, and that’s one of the reasons for having that stage prop that actually creates a little mountain where the tiger is sitting on top, in the tiger room. There was even a little staircase one could go up, symbolically. So, these elements were actually further extending the idea of this path or journey, and we can say that the entire exhibition is like a long scroll unfolding.

Cai Guo-Qiang. Inopportune: Stage Two, 2004. Installation view at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, 2005. Tigers: paper mache, plaster, fiberglass, resin, painted hide; arrows: brass, bamboo, feathers; stage prop: styrofoam, wood, canvas, acrylic paint; dmensions variable. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. Artwork courtesy of the artist. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: Can you talk about what’s happening in the tiger room?

CAI: Entering the tiger room, you see the violent act—tigers with arrows pierced into their bodies—and there’s a very visceral response. Even though it’s completely fake, the tigers are so realistically made that the audience feels pain when they see the them. The pain is not in the tigers, which obviously can’t feel. The pain is really in the person who’s viewing this. So, it’s through the artwork, because it represents pain, that one feels this pain and has this very visceral relationship or reaction to it.

There’s a lot of talk about the content of my work, about the subject matter or the historical background. But there’s not a real in-depth investigation into the visual impact. It’s through visual impact that you transmit these ideas. And it’s through visual impact that this pain is felt, and you can actually elicit a very direct response from the audience, a very strong response. But it’s the treatment of all the elements that has the power to do this.

ART21: So, for you there is a connection between aesthetics and power?

CAI: Maybe my work, sometimes, is like the poppy flower. It’s very beautiful, yet because of circumstances, it also represents a poison to society. So, from gunpowder, from its very essence, you can see so much of the power of the universe—how we came to be. You can express these grand ideas about the cosmos. But at the same time, we live in the world where explosions kill people, and then you have this other immediate context for the work.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2005 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.