Interview

“Bop” and the Process of Painting

Elizabeth Murray in her Manhattan studio, 2002. Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 2 episode, "Humor," 2003. Segment: Elizabeth Murray. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

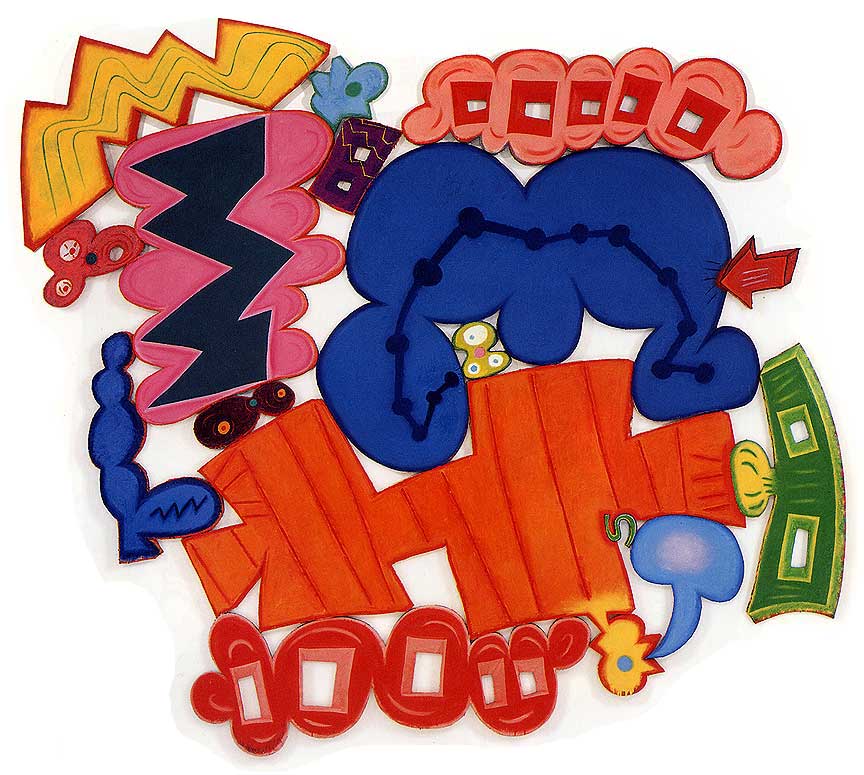

Elizabeth Murray discusses her 2002 oil on canvas painting, “Bop.”

ART21: Tell us about Bop. What’s the inspiration behind it?

MURRAY: Well, it has some predecessors. For a couple of years, I’ve been working with cutting out shapes and kind of glomming them together and letting it go where it may. Like, basically, making a zigzag shape and making a rectangular shape and a circular, bloopy, fat, cloudy shape and just putting them all together and sort of letting the cards fall where they may. And I don’t know why I am doing it this way. What I want more than anything else, in my life and in my painting, is—however I get there—for things to unify and for things to come together. And it felt—when I first started these, which was exciting—“Well, I am going someplace else now.”

I’m working flat. It’s not three-dimensional, even though the shapes are cut out and they have different kinds of perimeters. But I’m going to resolve these in a different way, and I don’t know how they are going to resolve. The psychological part of it was just starting something that I had no idea how to put together. Another part of it, for me, is to use very intense color, or different kinds of color—intense color, pastels. I’d never worked with pastels before, which I’ve always thought of as, like, sweet and cloying and sort of candy-like—not so much in this painting, but it has happened in some other paintings.

So, with the color and with the shape and with the drawing inside of the shape . . . Really, it’s just simply trying to make it work somehow. And letting myself really not know how it was going to happen, except that all of these shapes are stuck on to each other in some kind of way. Sort of like a weird fence or a weird lattice thing. And it’s been very frustrating and really fascinating, working into these paintings. And I’ve found, with this particular painting, that I just haven’t been able to stop on it, because I think one of the parts of working this way is that there are so many different combinations of things. It’s like being a safe-breaker in those movies, where they’ve got their ear up against the safe, and you are listening for the right click, for the right cylinders to drop down.

Sometimes it’s felt really like that, like I’m just painting and painting and painting until the right thing happens. And with all of my work (I think every artist has this): you leave it at night, and you come back and you think, “Wow, I’ve got it. I’ve got it!” And then you come back in the morning, and it’s gone; it looks awful.

Elizabeth Murray. Bop, 2002–2003. Oil on canvas; 9 feet 10 inches × 10 feet 10 1/2 inches. Photo by Ellen Page Wilson. Courtesy of The Pace Gallery, New York.

ART21: People are mystified by artists when they say, “This works, this doesn’t work.” Can you be more specific about that process?

MURRAY: Well, I think that what you are looking for—what I’m looking for—is resolution. And I can get it in my paintings, finally, for myself. In my life, it goes in and out. I have it one day, and I don’t have it the next day. But that’s why being an artist is so great, because you can get that kind of satisfaction.

The thing that has been hard about these paintings is that I don’t know how I am going to get them resolved. It’s like the resolution has to happen without anybody seeing it, not even me. But I know that it’s there; I feel that it’s there. There’s a moment when I start to feel it with this painting, and I don’t think I could describe it, but I do feel that with it. Because I can stop it; I can stop now. And when I look at it, instead of it being this battle or this conflict that I have to try to pull together, I can look at it peacefully. But then I feel like the challenge is: when you’re looking at it, what happens to you? Like, I’m passing it off to you now, and basically I am not really going to see this painting much anymore. Maybe two or three years from now I might be able to see it, if I saw it someplace, but it’s really kind of up to you. Because everybody will see it in a different kind of way, and it will mean different things.

I think it’s like that. You’re confronted when you are looking at a painting where you don’t have specific images, a face or a figure or a landscape. You’re confronted with something that you are challenged to resolve and unify in some way. Because there is a unity there—I keep harping on this—and that’s what has to work. What has to work is it has to resolve in secret, almost. There has to be resolution there. There has to be some kind of unification of the shapes and of the colors. And that’s the big thing. It just may be in a very surprising kind of way, in a way that you can’t really say, “It does this; it does that.” See how the red works with that green over there? See those three shades, and how it makes this arc across the space? And it’s not just formal. It’s an arrangement, like you’re arranging your living room or you’re arranging your face in the morning. It’s so integral to all of us—that kind of arrangement—that makes the form of the painting.

ART21: Can you quickly walk me through the process of making these paintings?

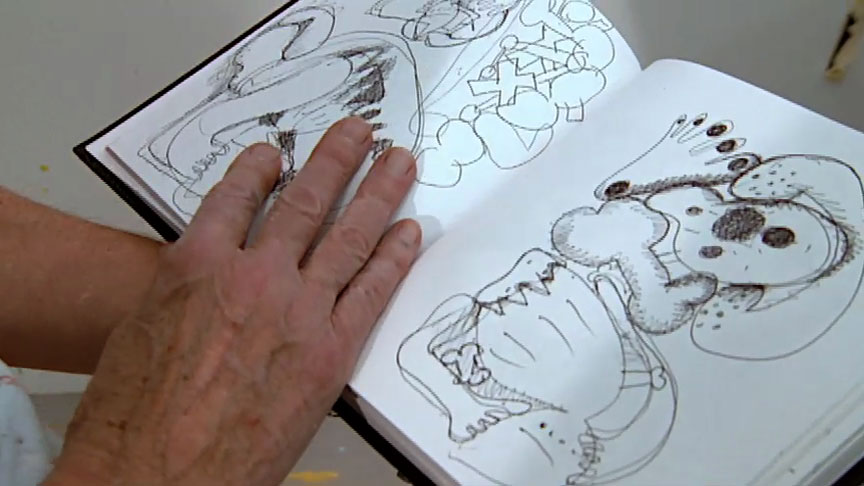

MURRAY: Okay. I start in one of my little notebooks. I just am scribbling around, get the idea, usually really quickly, and then I put it into my overhead projector and blow it up on the wall. I do a big drawing. Then I usually put another piece of paper over that and correct that and do another drawing. Then these two young artists, who are the carpenters, take the drawing to their shop and cut out the wood. And I go over at least once to see what they are doing when it is sort of three quarters through. Maybe I go over twice. Then they bring it back in. The forms are cut out of wood, like a regular stretcher except a cloud shape. They are really made exactly like that. And then they are covered with canvas and sized with rabbit skin glue and gesso. And then they come to me, and I start to work on them.

Elizabeth Murray in her Manhattan studio, 2002. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Humor,” 2003. Segment: Elizabeth Murray. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Do you ever change the forms once they arrive at your studio?

MURRAY: Sometimes I’ll take things away and add things right then. Usually I don’t change things until I start working on it. In this one, I didn’t change any juxtapositions. And I didn’t have any desire to. I mean, it’s hard to do—they’re wet, you have to take them off the wall, it’s really goofy to take things out, it’s a mess. But I do it. This other one—I took things out. We took it off the wall, and there were some other little pieces in it that are maybe in the first shots of this, and we removed those. And those are the only changes that I made.

ART21: These forms are somewhat abstract and somewhat recognizable. Tell me about this interplay.

MURRAY: I want both. I want all things. I want everything. I want to be able to say, “Oh, that’s a cloud with windows, or that’s just this floating, weird, bloopy shape with cutouts.” Because I enjoy that: I enjoy the possibilities of all of these forms. And this is absolutely from the past, too. You know, like, you get those books on how to do cartooning. You have a circle. Then you put two circles on top. And then you put a little nose in there and a little thing, and pretty soon you have Mickey Mouse. And that’s so much fun. I just like that. I don’t know if I could tell you more than that. And I think it is very obvious too, and I think it’s very corny. I just sort of accept, really.

ART21: The humor part of it—they’re serious paintings and they’re goofy paintings. Can you talk about that?

MURRAY: That feels like the very crux of it. I suppose that’s how I feel about life. You know—why do people laugh at Charlie Chaplin when he walks into a manhole? Like, what makes you laugh? It’s something about life and about accepting. Life is tragic and funny, and you get into horrible situations, and you go on.

I really feel very deeply, in terms of living, that it’s not something that I feel I have control over. I don’t feel like that’s a conscious decision. I think it’s a part in my work that I make conscious. Obviously, like, it fascinates me because I do it again and again and again, and it doesn’t make me tired. It’s my trying to understand what it is, really, that makes me do the paintings.

ART21: Was there any area of this painting that was horrendously difficult?

MURRAY: Yes. The whole painting was painful. When I did the drawings for this painting, I was very excited. They looked really great to me, and then I blew it up. And the guys who make these forms for me put it together, made it, and it came back into the studio. And the minute I saw it, I didn’t see how it was going to go together at all, even before I touched it. Just the way the forms were working—I just thought, “What was I thinking of? This is going to be horrible!” And it was really a long journey with this painting.

The colors I thought I was going to use—none of them worked in the beginning. But that’s nothing new. I found, instead of it seeming to get easier as I’ve gotten older, it’s really gotten harder. And I think it’s because I know a lot more. I’m much more demanding. I’ve done this, and I don’t want to go back into those places. I want something different. Even if it doesn’t come out different in the end, it has to feel different while I’m doing it. So, it takes me a longer time to kind of move through them. And there are just so many possibilities that I am aware of. And they are complicated paintings. I think these paintings are complicated; I don’t think they are easy to see.

Elizabeth Murray in her Manhattan studio, 2002. Production stills from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Humor,” 2003. Segment: Elizabeth Murray. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Do you think it’s because of all the parts and multiple surfaces?

MURRAY: Yes. I’m leaving out the physical air in between them, so they are like a kind of latticework or a sort of fence. And the way the wall works—the negative spaces really make a difference for these paintings. And intentionally each shape is, in a way, in conflict with the next shape. Even though, once you start to get into it, I think it’s pretty apparent that the round shape butts up against the hard shape. It’s soft and hard—just like we were talking about the goofiness and the more serious elements. These things are coming together. And it’s metaphoric really. Those are real metaphors.

ART21: What would you compare making a painting to?

MURRAY: Well, I think it’s really like playing. Really very similar to how a kid plays, somehow. You’ve got so many toys around. Carol Dunham was in the studio a couple days ago, looking at this painting, and he said, “You know, it’s like you are in your playroom, and you are just picking up these different shapes and throwing them on the wall and then putting them together and seeing what kind of a game you can make out of them.” I think that’s pretty explanatory of what it feels like to make them—and very close to the kind of feeling that I want to get out of them and I think I want you to get out of them, too.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.