Interview

Thinking with Clay

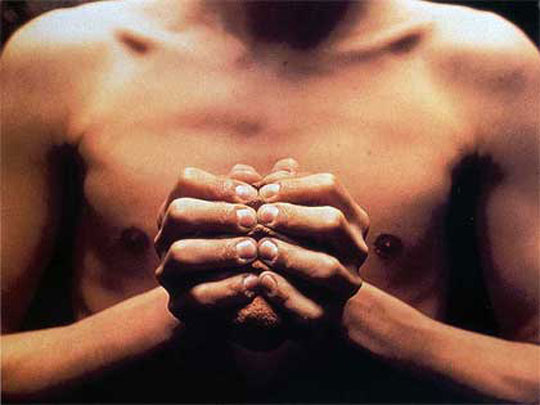

Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 2 episode, "Loss & Desire," 2003. Segment: Gabriel Orozco. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

In this interview, Gabriel Orozco talks about his process of working with clay, and what the tactility of the medium brings to his artistic practice.

ART21: How did you find the brick factory in France, where you made your clay pieces, and why did you choose to work there?

OROZCO: I was interested in working in a brick factory, more than a ceramic workshop. I was interested in the clay used to make bricks—more terra cotta, kind of porous, and more massive. I am interested in the weight of my hands in this clay and the manipulation of a certain amount of clay in relation to my body against a table and two or three spheres. So, this combination of elements: geometric and organic. Organic—my hands, my body. And geometric—the table or the spheres. And mass, which became a mass in movement, eroded by these forces. Normally when you do pottery, you try to make a pot or something, but you are very much aware of this empty center space. In this case, I was not so interested in the center, but a mass. That mass is compressed, moved, extended, eroded by these forces. And for that reason, I needed a clay that was special.

The workshop in France has this. It used to be a brick factory before, and now it’s a ceramic workshop. They have these machines to produce the combination of clay that I need, very fast. You can almost have a small industry or process. You can have this mechanically [produced] quantity of clay, and then my body can act mechanically. It was very important that my body become a kind of organic machine of constant movement, doing almost a mechanical movement with the clay—that constant. It was an activity that needed some rhythm—connected with the machine producing the clay, bringing it to the table, and then myself doing it—as a constant. So, in one day, you can do a whole amount of hours, like a worker doing a mechanical thing. And for me, that was important. Not so much one object, but more a kind of body machine doing this action with the clay.

ART21: Are you more interested in the activity of the making or in the end result?

OROZCO: I don’t separate the making and the final result; I don’t separate the two. I think the balance, for me, is very important—the balance of the making of something. This making is part of the final result, is part of the final end of the story. And that’s why, again, the body in action, the individual in action, in relation with the social space, the social materials, and economics of these is very important. At the end, you have an object, an installation, an image that reflects that relationship—between that individual, the social materials, the social displays—and the connection between dialogue and the negotiation between private space and public space in every object. And so, that’s why for me, the making of the work and the political implications of the making—how you make things—is part of the final result of the work. That’s why, you know, I don’t have a studio. But if I need a factory for something, or a workshop in France to produce this type of activity, I do it.

Gabriel Orozco. My Hands Are My Heart, detail, 1991. Two-part cibachrome; 9 1/8 × 12 1/2 inches each. Edition of 5. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

ART21: What’s the impetus for these pieces? You’re thinking of making some work, thinking of clay, and you have an idea of the result, your goal?

OROZCO: First, I decide where I would like to be, in terms of geography. That’s the first thing. It’s like, “Well, okay, I want to be by the ocean, or in the city, or in hot or cold weather, or I would like to be in the countryside or in the city for that time.” And then, also, at the same time, I’m working on ideas. So, I try to add my ideas to this location wish.

In the case of France, I wanted first to do this pottery project. I wanted to use a turn, which I never did before, and do these interventions with the pots in the turn, circulating. And then I was smashing it with things, and then I was doing other fragmented pots. I was interested in the pots. Then we found this workshop, and the clay that I needed was there. I choose a place because of the idea, but also because I wanted to be there, in France. If I really wanted to be in Mexico, I will do it in Mexico, which will be probably a different thing because of the different conditions of work in Mexico. At that point, I wanted to do it in Europe, and especially in France. So, it’s a combination of location and the idea and just finding that situation all together to make the work. But the idea is very important.

Gabriel Orozco. My Hands Are My Heart, detail, 1991. Two-part cibachrome; 9 1/8 × 12 1/2 inches each. Edition of 5. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

ART21: So, why pots? It seems so basic.

OROZCO: It’s the space of the pots, lately. I guess I’m thinking a lot about the pots as a space of transportation, conservation, everyday life, circulation. And in my work, the idea of all this is very important. Conservation, transportation—and the idea of roundness has to do with movement and transportation and circulation. So, my interest in the round or in the sphere and the circle has to do with movement and with erosion and the tendency of bodies to be round when they have to move, when they have to be exposed to contact with reality. That’s why I did the Yielding Stone, which is a Plasticine stone that, when it’s rolled, gets the shape and also all the dust. The contact with reality makes the shape of the sculpture.

In this case, the first idea was to make these pots, in which the turn and the circularity will make this void and this pot. Of course, they are not exactly pots. They are like plates, or they are just circular platforms in which I act, I do, I intervene. And then I call them pots because it’s easy and it makes sense, and it’s pots. But you can also see them as an abstract circular platform with movement and interventions. Like planets, or like disks, or like many other things. And that is a pot. A pot is a very complex instrument, and we see plenty in human history. And so, again, that can be related with Mexico if you want, but I think it can be related with Greece, and it can be related with everybody in the world because pottery is just part of history in general. And that’s my interest in it.

ART21: What are you examining when making each piece? How do you know if it’s done?

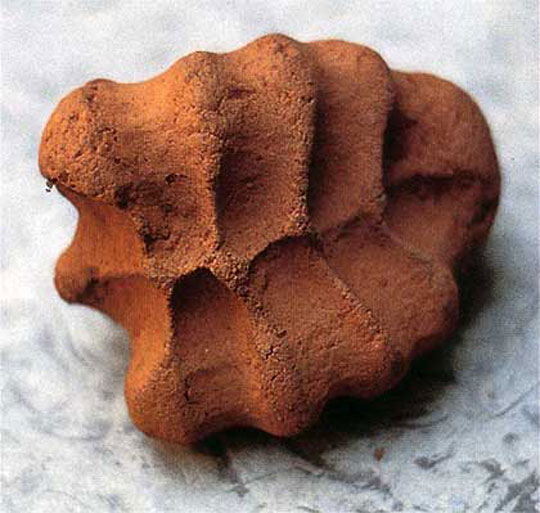

OROZCO: You get the brute industrial piece of clay, which is this square bunch of clay with no shape but the shape from the machine. Then I start to act on it, against the table, with the spheres, and with my hands. And with this movement, you start to get a dynamic sense of a body and of this space that is taking some shape. The clay is a recipient because it’s receiving all these actions and all these forces as a mass.

When I feel that it should be ready is a quite subjective thing. But it’s that the shape should represent what just happened before. And sometimes it doesn’t, because maybe I overdid it or maybe there were parts that lost their memory in the mass. So, when I finish doing this action with the clay, I just check around. I move, I walk around, and I see that every face and every part of the mass represents what really happens with clarity and simplicity, and that when someone else is going to walk around or is going to take it, they too can see what really happened. And that’s why, sometimes, it looks clear and then the piece is finished. Sometimes I have to do it again. Sometimes I can spend half an hour with one piece, and sometimes the other work is just in five seconds. But the criterion, more or less, is the work is finished when it represents what really happens in the action of doing it.

When an object has a logic on its own, it starts to talk of many other things. It’s not that it represents anything, but it represents its own reason to exist, in a way, as a material—as clay, terra cotta, in relation with bricks, in relation with construction, with pottery, with many things, and the body. Then it’s representing the movement that makes the shape. And then it can talk and express other things, suggest food, look like a fish, or something else. On its own, it has a finish and a reason that somehow justifies that it exists.

Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Loss & Desire,” 2003. Segment: Gabriel Orozco. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: For the viewer that sees the completed show of these clay works, how are you thinking that the person will respond? Are you interested in the response?

OROZCO: Sure. Yes. Art happens in that space between the spectator and the work. It’s that space in between that finalizes the work of art. And in the case of the terra-cotta works, they are especially artistic—on the one hand very artistic, on the other very hermetic.

But then, they were also for me very mysterious. I was trying something I never did before. When you are doing this, you are doing it for yourself, because you will be a spectator also. And when you finish this that you are trying, you will also be in the position of the spectator. And I don’t like the word spectator, because a spectator is passive, and I don’t think the spectator should be considered passive. It should be more like activator or something like that. So, it’s that person who is going to activate that work or the object or the photograph in their brain, and they’re going to start to make it work, make it happen, in terms of memory, emotions, et cetera.

As an artist, when you do something that didn’t exist before or that you never saw before, you need to do it because you are going to later on be the activator of that. I see it for the first time after I finish, right there, fresh. And sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t. It’s a subjective thing. Sometimes I let it go even if it doesn’t work so much for me. I say, “Well, let’s wait and see; just take it out.” In the case of the clay pieces, I am quite easy with them. I let them go. And I take it quite light, in that sense. Just go on, see what happens.

ART21: What happens after you think a piece is ready?

OROZCO: After I feel it’s ready, when the action is enough in the clay, then I just go for the next. And then this one goes out and has to dry for two months because there’s quite a lot of water inside the clay; and it’s massive, and so it has to dry for a long time. And we fire the clay with wood. The firing is also hazardous because there can be quite a lot of accidents, and it can crack the piece, and also the color variation is uncontrollable. That is nice, too. It really looks like a brick—the different tonalities. It’s a very straightforward process: classic, simple. I’m not so interested in colors and finishes. It’s just a regular kind of brick production.

ART21: When you installed the show in the gallery, what decisions were you making?

OROZCO: In this case, I decided to use market tables that are quite common in Paris. They are wood panels with metal legs, and they use them in the markets outdoors. So, there is the transportation—very flexible, very easy to move. So, I display these tables, and on each table, I put one or two pieces. I think this was a nice connection because some of the pieces look a little bit like food, or bread, or fish, or a recipient of some kind of food. And then I thought it was appropriate to have that reference to all these things in the market. And in the case of the piece in Documenta, it was altogether a group of forty variations of plates and pottery. And in this case, they were more like single pieces on tables.

ART21: Were those allusions to food intentional, or did they just happen?

OROZCO: I think they just happened. I was not thinking so much, when I was doing the work, that it has to look like bread, or it has to look like a fish, or it has to look like anything. So, when I was doing it, it was more subjective, just like doing it in the moment. It depends also on the firing, with the color and the final shape. Some of them came out the way they did because firing clay is a very similar process to how they prepare bread or how they cook. It’s similar, how I manipulate these things and how people do food and prepare things. So, in the end, it looks like that because the process of the movement of the hand is quite common in many activities. So, then you have this shape. But it was not intentional in terms of imitating. It was just a consequence of a common logical activity.

Gabriel Orozco. My Hands Are My Heart, 1991. Terracotta; approximately 6 × 4 × 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

ART21: Could you talk about the process of making things with your hands versus a mental, thinking process?

OROZCO: The thinking process has many levels, and I try to explore how it is related to the body in many different ways: to be static, to be seated, to be walking, to be moving, to be looking at the ocean, in a train. To be working with my hands in a drawing, like a concentrated field, or in a more expanded field with objects in a situation, or with the clay and very physical . . . This all generates a stimulus in the brain, and you are thinking. But the connection between the brain and the body and the breathing and the sweating and the time that you spend and how you slow down thinking or you accelerate thinking is very important for me because you just generate the different aspects of thinking. I am interested in all of them. I try to combine them because I cannot just be thinking statically. And I cannot just be writing. I like to move, and I like to be more physical.

I think, in the final result of the piece, the thinking process should be evident. It should be evident, the brain that did that work. Not just the hands, not just the mold, not just the physical and technical aspect of the making. It’s much more important that the intellectual aspect of the making of the work is evident in the final result of the work. I think that is what is really going to generate the space of communication, when someone looks at something that makes thinking happen in the receptor. The shape at the end has to do with provoking the space for thinking.

That’s why I’m not so much concerned with words in my work, because I don’t think I need words in the work to generate thinking. I think you can do it through the objects. If the objects have content and some serious thinking involved, then they are quite open to receive new thinking from the visitor.

ART21: Was there an underlying order or relationship to the placement of clay works on the tables?

OROZCO: No, there wasn’t a specific order. I wanted it so that you can see each one separated as a single work. So, you can walk around, and they are on the table. They were made on a table. So, the height and the space of the table are just the appropriate space and height for the work, because it’s how I was looking at it when I was manipulating it. And the table is very important in my work in general. I have these working tables and I work on a table. And for me the table is this platform of action in which we do so many things. That is very important in my work.

In the show, I did try to make connections with the photographs that I took in Mali in July. I did this trip to Mali for three weeks, and I took some photographs that are connected with the work. And they are very different, but there are some connections. Like the cemetery of Timbuktu, which I found on the trip; I found this cemetery because I was interested in the pottery and the ceramics. When I did this trip to Mali in Africa, the reason was to search for ceramics traditions, to understand, to learn, to enjoy what they do because it’s a great tradition in Mali. And then I discovered this cemetery in Timbuktu.

It’s interesting how the work takes you to discover places that you would never discover if not [for] doing this work. So, that connection between what you do and what you discover afterwards is very interesting. In this aspect, in the show, you have these tables with these ceramics on one side. And on the other, on the walls, you have these photographs of Mali. There isn’t a direct connection. But there is something that is: evidently, the same person who is interested in these things. And there are many reasons for that.