Interview

Power, Feminism, and Art

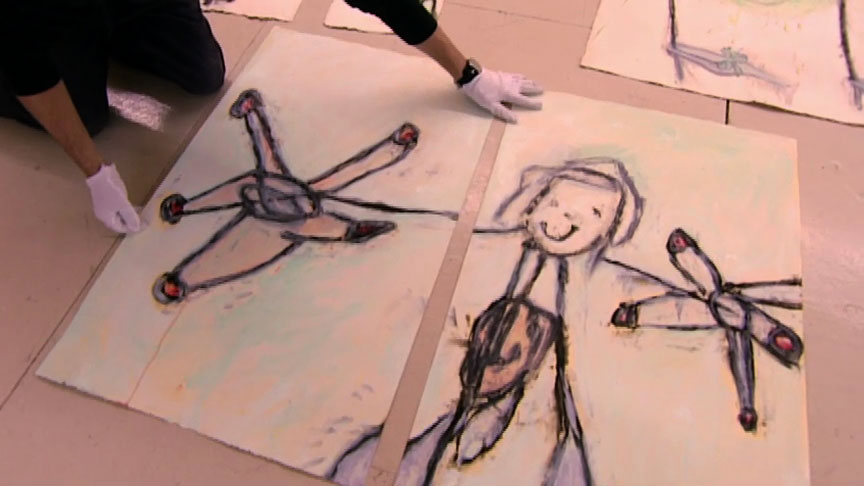

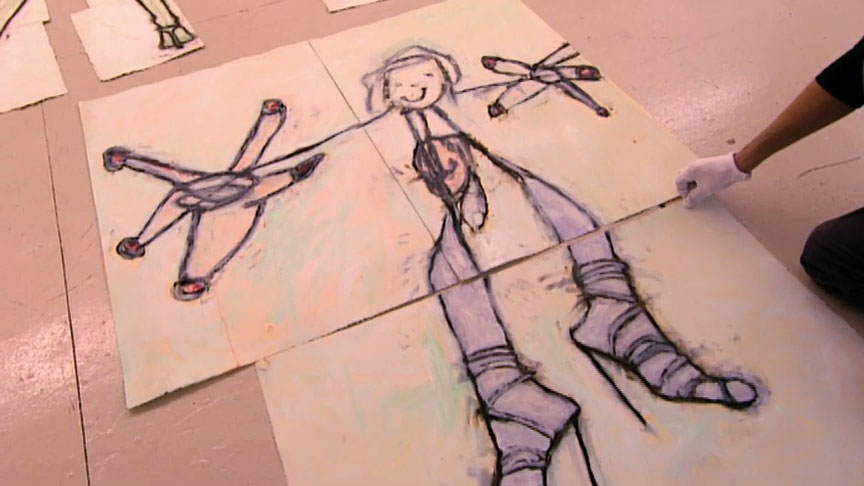

Ida Applebroog in her SoHo studio, New York, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power, 2005. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

Ida Applebroog shares her experiences starting out as an artist in the 1970s and the ramifications of power and tokenism in art.

ART21: Can you talk about first making art when you moved back to New York in the 1970s?

APPLEBROOG: As I said before, now I consider myself a generic artist. When I started out, I came to New York in about ’74. At that time I didn’t know anyone. I was a New Yorker, but I’d been away for a long time. So, I came back and I really didn’t know how to enter the art world again. I was in the art world, so I shouldn’t say again, but what happened was that I started to go back to my roots, just doing drawings, and for me it was like instant coffee—I can just draw and draw forever.

From these drawings I started making books. Being in New York and not knowing anybody, I had access to a printing press and would mail them to people I did not know: artists whose work I really liked, people writing who I thought were interesting. I think I sent out mailings—one every few months—and suddenly I was, I guess, a nuisance. (LAUGHS). Next, I went into doing videos—narratives and videos. Then I worked on three-dimensional vellum paper sculptures. I’d fold them in such a way that they became stagings. And working with the vellum, I used to put layers of Rhoplex on. At one point, they took Rhoplex off the market because it was supposed to be carcinogenic and I thought, “No, I’m not going to use that,” so I tried to simulate that stroke in paint. And then people liked to call me a painter.

I still feel I’m not really a painter. When I work with canvases, I work with three-dimensional structures. It’s about structures. It’s about stagings. It’s still—it’s always about stagings. No matter what would happen to my hands or the rest of my body, I’d still have my mouth, and I can still plant a pencil in my mouth and work. It’s like anybody that creates: they’re going to find a way to create and it doesn’t matter how. Now that I’ve given you that sermon…

Ida Applebroog in her SoHo studio, New York, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power, 2005. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: The word power: does it resonate for your work?

APPLEBROOG: I like the idea, the power part. And it’s the kind of thing where, every time someone asks me what my work is about, I always say, “It’s hard to say what your work is about.” Nobody really wants to say it, or they make up something that they have stuck in their heads that would sound right. But for me, it’s really about how power works. And I learned that at a very early age. I come from a very rigid, religious background. And it’s the idea of how power works—male over female, parents over children, governments over people, doctors over patients—that operates continuously. So, it’s not as though I set out to say, “Well, let’s see what the power balance is between this piece in my painting and that piece in my painting.” This is the part we’re talking about: that you never really know what you’re doing until at the end you realize, “Ah, that’s what I’m doing, that’s what I’ve done.”

ART21: When you look back at the work, how do you think about being a female artist during a time dominated by primarily male artists?

APPLEBROOG: Coming out of the ’50s, women were pretty invisible. Women had a certain role in life. No matter what school you went to, you had to make certain recipes, make sure that you got married, had children. The war was over, and Rosie the riveter was over. The working women were gone, and the men came back from war. I mean, I was a child, but I still lived through all of that. And it never occurred to me that anything was wrong; that’s just the way things were.

When I went back to school, I was in my thirties, about thirty-five. I went back to the Art Institute in Chicago. I used to be flattered when a teacher would say to me, “Oh, your work is so interesting and good, it looks just like a man’s.” And I was very, very flattered—“My work is good; it looks like a man had done it!” It took me a long time to resent this and realize what Betty Friedan had said: Women have a condition that has no name. I realized at a certain point, “Yeah, I know what that problem is, and I don’t know what the name is, but I have it.” And coming out of the ’50s and going into the ’60s, it was an incredible time for me to understand how power worked or how power can work. A number of years back, a piece was published in The Village Voice. It was by a male critic, and he said biology is destiny: women don’t have the physicality or eroticism to be painters. It was a long time ago, the ’90s. I hope by now he’s been somewhat radicalized. In those days, we had a lot of very strong women painters around—Susan Rothenberg, Elizabeth Murray—so to have read that was incredible!

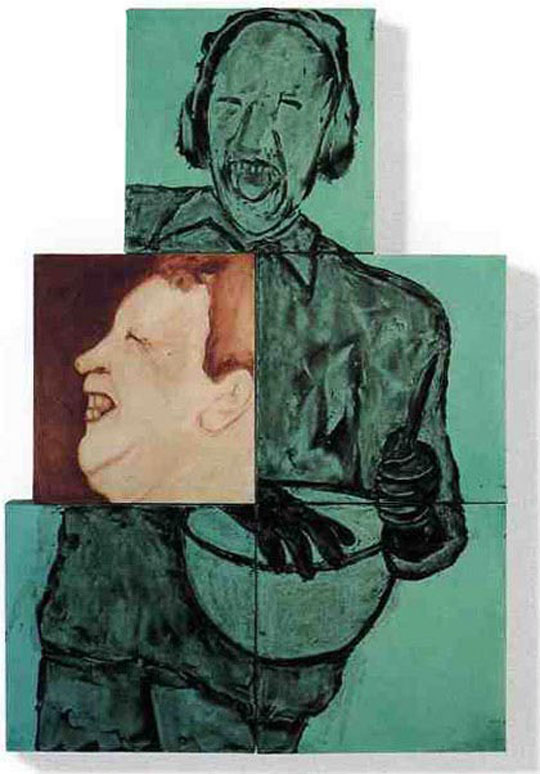

Ida Applebroog. K-Mart Village III, 1989. Oil on canvas; 5 panels, 48 × 32 inches overall. Collection of the artist. Photo by Jennifer Kotter. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

ART21: Did the feminist movement change the work?

APPLEBROOG: I want to tell you something. I have a real problem with feminism and art. This is something that I’ve always objected to. I never liked the all-women shows. It really does label us, ghettoize us. There are many women around that say “Don’t call me a feminist, that’s a dirty word; let’s not discuss feminism.” And a lot of the younger artists—not that they say that, but they feel: “It has nothing to do with us anymore. We’re able to do all this; we’re able to go out there; we’re accepted; we are the gallery system.”

I remember when Pace had a full-page photograph of his gallery on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. It was all male, but I think there was one woman at Pace at that time. I don’t remember who it was . . .

ART21: Agnes Martin?

APPLEBROOG: Oh, Agnes Martin, of course! The ’80s were a very interesting time because of what happened to the art market, what happened to women. All the things that they worked towards in the ’70s—feminism, Minimalism, Conceptualism, and performance art—it was very exciting. And then came the ’80s, and it became very market driven. I think we lost a lot. Now I hope we’ve reclaimed some of that.

ART21: What about feminism and you?

APPLEBROOG: No, I don’t want to be placed in that crack. I don’t want to have to give anyone that kind of a handle, to place us in such a way that it ghettoizes the entire way of thinking about who’s making art, how art is made. You can make art from today until doomsday, and if they only place you in a show that is about women artists, if that’s the only thing that happens, the only place that they put the women, we’re in trouble. It feels like tokenism again. And it really distresses me.

Ida Applebroog. Marginalia (Isaac Stern), 1992. Oil on canvas; 2 panels, 35 × 39 inches overall. Photo by Dennis Cowley. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

ART21: Would you consider yourself a political person?

APPLEBROOG: I don’t even like the word political! I don’t like any words. No, I hate being labeled. I really hate being labeled. I do a lot of work on violence all the time, you know. I’ve also had that come at me: “Why are you so obsessed with violence?” And you know my answer? I look at them and I think, “Why do you say I’m obsessed with violence?” I live in this world; this is what’s going on around me. I can’t change that.

So, when I’m doing the work, it’s like I’m in the studio and I have all this stuff on my back. I have all this baggage, and I try desperately to start working. I’m carrying in how the postman looked at me that morning, what happened in my personal life, what did my dealer say to me, what did my friend say on the telephone—all the different things that go on in your mind: What do I have to do? What appointments do I have?

And then how do you get to do the actual marks on the canvas—where that [baggage] disappears? It takes a long, long time. And then this is not really what you’re doing, but in a way it’s like peeling off the layers, peeling off the layers. And finally you’re not conscious any more of anything being there, and you’re free and you’re working and you don’t know that time has gone by—and it’s hours and hours and hours. But then you have to go back into the real world. And the real world is the world that the six o’clock news is about and your own personal life, because your own personal life is involved in that, also.

Interviewer: Susan Sollins. Originally published on PBS.org in September 2005; republished on Art21.org in November 2011.