Interview

Influences, Train Marking, and Graffiti

Margaret Kilgallen in her studio, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Margaret Kilgallen discusses her influences and the goals she worked towards in her art.

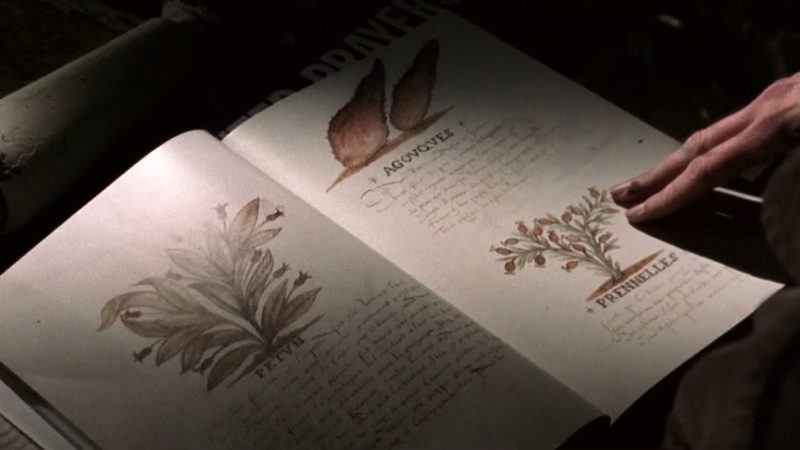

ART21: You have many books here in your studio—very eclectic, like this one—it’s a very old natural history book.

KILGALLEN: Oh, of the Indies, probably. I don’t know, French. When I first started painting seriously, I used to look at a lot of typography from the sixteenth century, fifteenth century. I was interested in manuscript painting, and the lettering that is on the manuscripts, and the color of the page, and the color of the inks that they used, which were normally black and red and sometimes blue. That sort of tied into bookbinding, for me, and the type of typography that I would see in books I’d repair, or the old pages of the books that I would repair. And that also relates to this book here. I think part of the reason it’s so beautiful is that the pages were printed like they are in the manuscripts, so they still show the age that they are. And they also show the bleed-through of the ink on the back. The imagery is really kind of simple and graphic and descriptive of what was natural in the life of the people living in the Indies. But what I like about it is how simple and graphic the images are.

ART21: The way these images are made reminds me of your work—straightforward and yet stylized. Very flatly painted.

KILGALLEN: Having a background in doing printmaking and letterpress, I think that I became very interested in images that were flat and graphic. And my painting, still today, is very flat. I think part of the reason is that, often in books that show descriptive plants and animals, the images tend to be very flat. I was deeply influenced by that. American craft is like that, too; the painting is very flat. And also the painting that you see on the storefronts, handmade signs, tend to be very flat. That’s probably my biggest influence, you know, those things.

Margaret Kilgallen in her studio, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: Do you have goals in your work, things you are trying to achieve?

KILGALLEN: I think when I think about myself, I feel I have very short-term goals. And, let’s see …I… you know what? I think I’m not answering your question.

ART21: No, you are…

KILGALLEN: No, I do have something to say about that, but it relates to what I said to you earlier in the train yards, about women. I guess it’s not really a long-term goal, but when I get down and don’t feel like doing art, and I feel like giving it up, then the thing that keeps me going is the fact that, maybe, somebody will learn either from what I’m doing or from seeing my work. I don’t know how to say that, exactly. Often, I know, artists supposedly do their work for themselves, and it is very personally motivated, and you work a lot by yourself. And yet, when you put your work out there, and somebody comes up to you and thanks you for doing it, and especially when young people come up and thank me—that is why I do work, if I can inspire somebody. I think my work, in particular, is pretty accessible to people, and I think it’s very accessible to young people who are interested in doing art or are doing art.

ART21: You seem interested in signage and other things from forty or fifty years ago.

KILGALLEN: I’m definitely interested in the past and in a past that, maybe, I idealize as a time when things were well made. And when, maybe, you couldn’t go to Home Depot to find what you needed, but you had to make it on your own. And the thing is, often people refer to that as the past, and I don’t really think of it as the past because people still do that all the time today. It’s just, often in the city, when there’s so many things to look at and so many things going on, you don’t see those things. But I see those things. On any day in the Mission in San Francisco, you can see a hand-painted sign that is kind of funky. And maybe that person, if they had money, would prefer to have had a neon sign. But I don’t prefer that. I think it’s beautiful, what they did and that they did it themselves. That’s what I find beautiful.

Work by Margaret Kilgallen in her studio, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: You like to see the touch of someone’s hand.

KILGALLEN: Yes, I enjoy seeing… I don’t know how to phrase it. I like things that are handmade, and I like to see people’s hand in the world, anywhere in the world; it doesn’t matter to me where it is. And in my own work, I do everything by hand. I don’t project or use anything mechanical, because even though I do spend a lot of time trying to perfect my line work and my hand, my hand will always be imperfect because it’s human. And I think it’s the part that’s off that’s interesting, that even if I’m doing really big letters, and I spend a lot of time going over the line and over the line and trying to make it straight, I’ll never be able to make it straight. From a distance, it might look straight, but when you get close up, you can always see the line waver. And I think that’s where the beauty is.

ART21: But when it comes to graffiti, people, especially adults, have a hard time seeing the beauty in that sort of gesture.

KILGALLEN: Well, when I think about my parents… My parents don’t understand writing on things, like writing graffiti, but they’re beginning to.

Margaret Kilgallen installing work at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: What’s making them think differently?

KILGALLEN: I think, when I have explained graffiti to my parents and compared it to the barrage of images we see every day, especially advertising. And how on billboards or corner stores or anywhere, it’s absolutely everywhere, and yet it doesn’t bother anybody. We completely block it out as if we don’t see it, but for some reason we don’t think of it as garbage. And instead, maybe, we look at graffiti, or the public looks at graffiti and sees garbage and ugliness. And I always wonder why they don’t look at the billboards, especially around San Francisco. There are millions of them: like, the new thing is dot-coms everywhere. Like, why isn’t that garbage? That’s like mind garbage. It’s like commercials on TV, and yet nobody ever questions that. That is so a part of their view of the world, every single day. And when I explained that to my parents, they began to understand why other people might want to put their own visuals in their own neighborhood, something that they could relate to.

ART21: Like the markings on trains? What are those visuals about?

KILGALLEN: Writing on trains, or train marking, is like networking. I’m talking specifically about the markings on the trains. First of all, I always find it amazing that I see things that I recognize, and I see things again and again. Because if somebody’s living in Maine, it’s pretty amazing that it arrives in San Francisco intact, and I can read it. The oldest things I’ve seen have been from the early ’70s and maybe late ’60s. When I see things I recognize, I don’t know anything about the person. I just know what they write, and it’s kind of like meeting an old friend. There is not specific communication that goes on between people, but you have a sense of anybody who’s spending so much time writing on trains because, if I’m to walk into a yard and see something in California, that person most likely has written on hundreds of trains.

ART21: How is marking on trains different from marking or doing graffiti on the streets?

KILGALLEN: It’s not that different. It’s actually very similar to what happens in the city except for most of the people who write on trains tend to be older males. They’re not young males. They’re older males.

Margaret Kilgallen in a Bay Area rail yard, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: I know you had some hesitation doing this television program, and now maybe I have a better sense—knowing the way you feel about commercials and billboards and the fact that you don’t even watch TV.

KILGALLEN: I felt really shy and nervous about doing this particular TV thing. And the reason I decided to do it was because I believe there need to be women visual in our everyday landscape, working hard and doing their own thing, whether you like it or not, whether it’s acceptable or not—working hard, doing their own thing. And I hope by showing my work anywhere I happen to show it, that there’s somebody who can come away feeling like they can work, too. And I especially hope to inspire young women because often I feel like so much emphasis is put on how beautiful you are, and how thin you are, and not a lot of emphasis is put on what you can do and how smart you are. I’d like to change that, change the emphasis of what’s important when looking at a woman.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.