Interview

Collaborating with Strangers

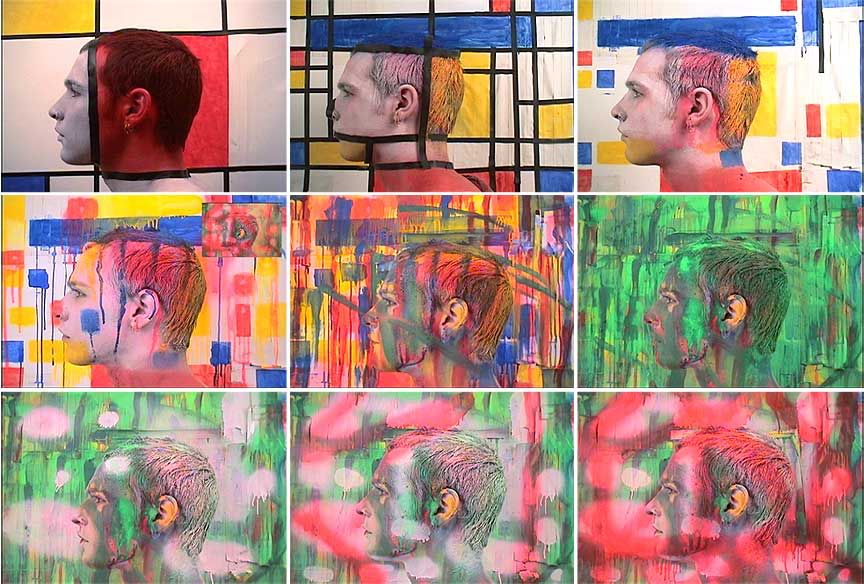

Oliver Herring. The Sum and Its Parts, 2000. Total running time: 10 minutes, 35 seconds, looped. Edition of 10 with 2 artist prints. Courtesy of Meulensteen, New York.

Artist Oliver Herring discusses what it’s like to invite strangers in as participants in his video and photographic work.

ART21: Talk about what it’s like, bringing strangers into your work.

HERRING: The hardest thing is to work on a level of trust, especially with strangers. There is a level of expectation that can be very hard to meet. The premise is to make a video, but that can mean a lot of different things. Perhaps it sounds much more glamorous to some people than it is—especially the videos that I make, which are stop-motion. I repeat a lot of movement—and whatever we end up doing—because I don’t know where it is going. I try to take my cues from the personalities of these people. So, if I have two people whom I know in the studio, I can circumvent that whole issue and go straight to having fun. Ultimately, that’s where you want to go—to that place where you enjoy it, where you’re not self-conscious, where personalities come through. At some point, you reach a point of saturation where you’re so tired and exhausted that the last little bit of guardedness falls away and something really pure comes out. That’s what gives these videos humanity. And that’s what I’m shooting for. All the action—all the motion—is really just a decoy to get to that.

In the end, these things are collaborations. I don’t think of the people I work with as models or actors. They are people who are willing to sacrifice their time for me. Of course, there is something in it for them, too: the experience is intimate and unusual. But it’s the same for me. Although I know more what to expect, since I usually work with strangers, there is still a whole new world that enters my studio with whoever comes in. It’s very adventurous.

ART21: Are there times when it’s difficult to work with other people?

HERRING: It’s like walking a tightrope. On one hand, I feel I have to be really selfish. If I sense some potential somewhere, I feel I have to go with it. I owe it to everybody’s time spent together. Ultimately what I want is a good video, a good piece of art. But at the same time, I’m trying very hard to keep everybody entertained, and that’s hard sometimes.

I had a shot where I had almost forty people in the studio, and it just didn’t work. So, I ended up working with six or seven people, which made it really hard. There was a lot of footage that I shot that never made it into the final piece that I just did because I felt I had the obligation to do something. It’s a balancing act, and since I’m not very scientific about anything, I just have to go with my feelings. If I see somebody really fidgety, I try to engage that person somehow.

ART21: How should people think of your videos in relationship to your other work?

HERRING: I look at my videos as a continuation of my work in general. My work has always been very stripped down. It’s always about generating something with a very simple and accessible material, or with what’s around me. And perhaps the more “operatic” video pieces were a reaction to my knit sculpture, which kept me isolated for so long in the studio that the videos were a way for me to be social and flamboyant and to change my mind all the time. Because when I did the knit pieces, once I committed myself to a piece, I was locked into an idea, and the only thing that could really move was my mind. The early video pieces were a way for me to express what was going on in my mind. One of my first videos, Exit, literally starts out with me sitting in the chair that I usually knit in, and then it turns into this flight of fancy—certain fantasies that I dreamt about while I was knitting.

ART21: What is your process for making a work?

HERRING: I tend to start out with a lot of artifact because I find comfort in that. Then I slowly move away from it. Once I reach a certain comfort level, I end up with nothing because it’s the hardest thing to gain something from. If you have nothing around you, and you can make something out of it, that’s hard but also very satisfying—because it’s ultimately very uplifting. But you have to work for that. So, I usually start with something and then strip it away to nothing, just trying to generate something out of the air. I try to rid myself of excess. It’s the same with everything that I do. I just like when things are really boiled down to an essence—because to me there is so much more truth in it.

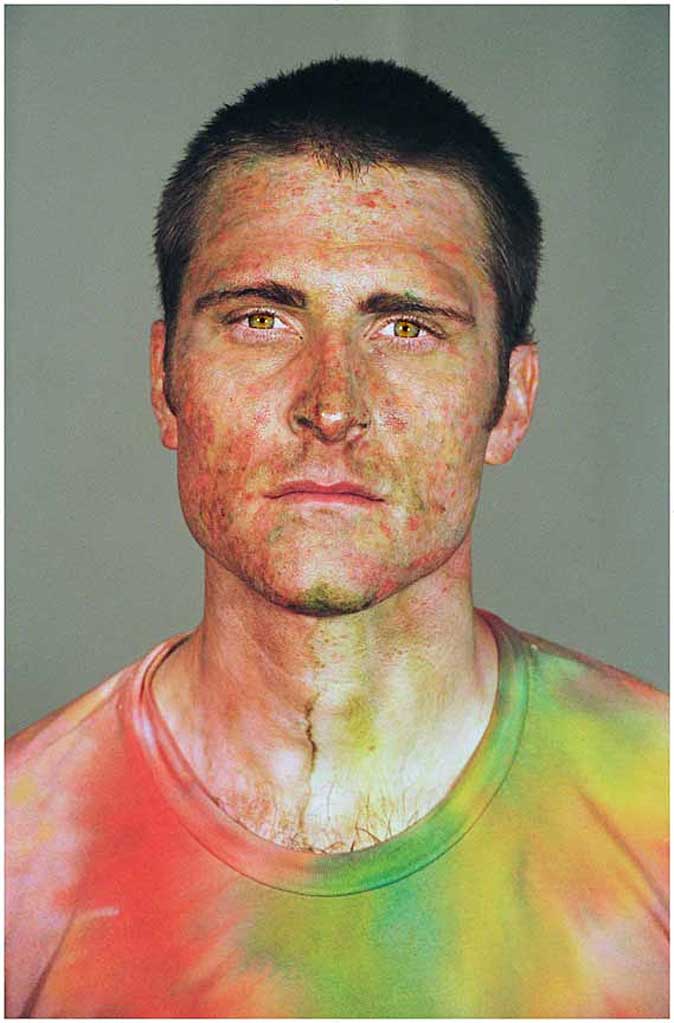

Oliver Herring. SHANE AFTER HOURS OF SPITTING FOOD DYE INDOORS, 2004. C-print; 41 1/2 × 62 1/2 inches framed. Edition of 5 with 2 artist prints. Originally commissioned by Artpace San Antonio. Courtesy of Meulensteen, New York.

ART21: Are there ever conflicts in these collaborations?

HERRING: I think sometimes people might be frustrated when they’re not used in the way they imagine themselves. When I allow people to do in front of the camera whatever they want to do, it becomes so complex, eccentric, and playful. I feel when I impose my ideas, it actually becomes much less so.

People seem to have a pretty clear idea of themselves, of how they want to be portrayed in front of a camera, which is a very interesting relationship between people and cameras. It might also be a generational thing. Younger people who grew up with TV, video cameras, and reality television have a very clear idea of how they want to be shown in front of a camera, whereas slightly older people might not. So, that’s where the frustration level might come in. If somebody is not portrayed in the light that they expect, then it might be frustrating.

On the other hand, the videos that I end up editing and showing tend to be good enough. I think everybody seems to be very happy, because they always come back—that’s the other thing. The video that they’re shooting here today is actually an example of two people who have been in quite a few of my videos now.

ART21: Describe some of the materials you use.

HERRING: At this point, nothing—nothing at all. I used to use ten, fifteen pieces of cardboard that I would recycle. It almost became a challenge to find new usages in those ten sheets of cardboard, to see how much I could get out of them. But at this point, I’m really just trying to rely on people’s personalities and also my (hopefully) sharpened instinct to deal with people. I think that’s the other thing that I’m trying to cultivate: how to deal with people successfully.

ART21: How do you see your role in creating the videos?

HERRING: I still think of myself very much as a sculptor or a painter. The idea of a director seems too hierarchical. I can’t relax into that at all. And maybe that’s also why these things become very collaborative. While I call the shots, I do it under disguise. I don’t really know what my role is, and perhaps that’s a good thing because it keeps me fluid and changing—behind the camera or in front. It leaves doors open. I don’t like roles, actually.

ART21: Talk about how you arrived at stop motion as a way to structure your videos.

HERRING: In formal terms, it was logical because my knit work was incremental and built from little moments that in a linear way added up to a larger picture. Film is very similar. Stop motion communicates that even more clearly because you have one moment that is still and then another moment. So, it’s almost like one still life that’s bunched together with another still life, and so on. In between, I can rearrange and manipulate. Since I work on a shoestring budget, I deliberately try to keep things as simple and manageable as possible. I’m not interested in technology and all that—I mean, I am, but not for my work. I try to make things with my hands and to impose that kind of feeling and tactility onto my videos. Stop motion gives me that luxury because I can build a still life of sorts and then change it. I made a little document by photographing it and by filming it, and then in the film, it sort of adds up to a larger picture.