Interview

Just an Artist

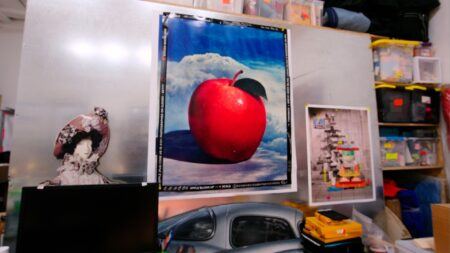

John Baldessari at Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, 2008. Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 5 episode, "Systems," 2009. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

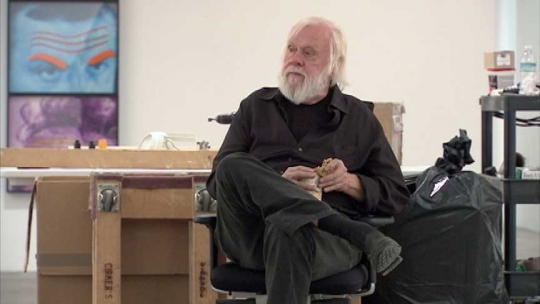

John Baldessari discusses language and communication, and how many years of teaching, from preschool to college level, influenced his work in the studio. Interview by Susan Sollins at the artist’s studio in Los Angeles, California, July 2008.

Art21: I’m curious about your longtime interest in language. Were you always fascinated by words?

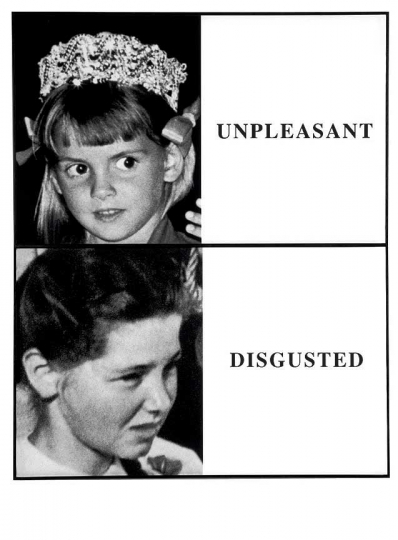

Baldessari: It might have started back when I was painting, this idea, which wasn’t unique to me, that language could also be art. I never quite understood categories. Words are a way we communicate, images are a way we communicate, and I couldn’t figure out why they had to be in different baskets. I was getting tired of hearing the complaint, “My kid could do this,” and “We don’t get it. What’s modern art? Blah, blah, blah.” And I wondered what would really happen if you gave people what they wanted, something they always look at. They look at magazines and newspapers, so why not give them photographs or text? That was the motivation and when I moved in that direction, thinking about language—and I don’t know exactly how this happened—it seemed to me that a word could be an image or an image could be a word. They could be interchangeable. I couldn’t in my mind prioritize one over the other.

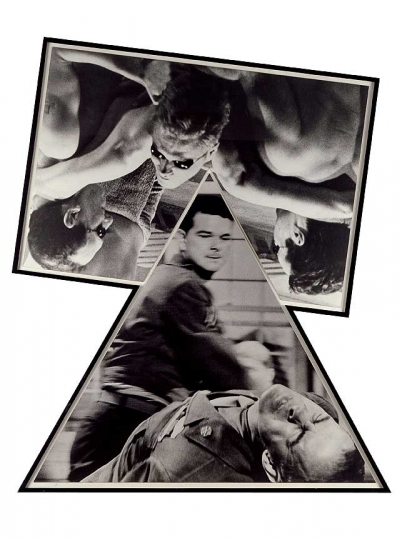

For a lot of early work, I would have files of photographs that I would take off TV and then I would have an assistant attach on the back of the image a word that she thought could be its surrogate. And then I played: I would make a sentence out of the words. And then for that sentence, I would use the images instead of the actual words, kind of flip-flopping. In my multiple image pieces, I probably had the idea that there was a word behind them and I was building blocks or frames. I don’t do this so much anymore, but some parts of my work are multiple frames that I’m probably building like a writer or poet builds with words. That’s a description that seems to make me feel comfortable. And I still have the idea that an image and a word could be interchangeable.

Art21: How do you feel about people applying the term “conceptualism” to your work?

Baldessari: I think isms—impressionism and so on—are useful for writers when something seems to be brewing and they want to give it some sort of generic title. I think with conceptual or minimal art or the period when I began to emerge, I just got put in that basket—that I was a conceptual artist because I used words and photos. But as time goes on you begin to see the artist more distinctly and realize that the labels don’t really apply. And I think if you asked any artist that you might think of as conceptual now, if he or she would use that term, the answer would be, “No, I’m not a conceptual artist.” Once I said to Claes Oldenberg, “You’re a pop artist.” He said, “No, I’m not; I’m an artist.” And Roy Lichtenstein said the same. I have the same feeling. Conceptualism doesn’t really describe what I do. If somebody wants to use that term, it’s fine, but I’d prefer a word that’s broader and better. I’m really just an artist.

John Baldessari, Prima Facie: Unpleasant / Disgusted, 2005. Archival digital print on ultrasmooth fine art paper mounted on museum board; 55 1/2 × 42 1/4 inches. © John Baldessari. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

Art21: Tell me about growing up in a small town and moving back there after college?

Baldessari: I was going to Otis Art Institute and I got tired of that after two years of living in Los Angeles. I needed a job, so I started teaching in San Diego public schools. That put me back in National City, where I was born. At the time I felt pretty isolated, but looking back on it, it was very valuable. I had the idea that I would just lead a normal life in National City. You know, I’d get married and have kids, paint on weekends, teach high school, and that would be it. But my life began to change after I moved back. I thought no one was looking or listening at that point, so I decided to use text and never touch a canvas. I hired a sign painter to paint the text for me and I’d purposely say to the sign painter, “I don’t want it to look decorative in any way but more like ‘keep out’ or ‘no trespassing’ signs.” I don’t think I could have gotten away with it in Los Angeles, because I’d be aware of all of the art around me and I probably would have been laughed at. In fact, when I tried to show my work around galleries in Los Angeles, that was pretty much the result. I’m glad I stayed in National City because I was able to find out what was bedrock for me about art.

Art21: So what was bedrock?

Baldessari: That art making is essentially about making a choice. I felt that was fundamental.

Art21: My guess is that when you were a teacher you did a lot of provoking, provoking students to think and to look. What age groups did you work with?

Baldessari: I’ve taught every level imaginable. I got my B.A. degree at San Diego State University and I began teaching right away because one of my instructors got ill and asked me to take over his classes. My second experience was teaching a Saturday life drawing class at the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery. Then I got a job teaching in San Diego public high schools. And then I taught at the La Jolla Museum for preschoolers, a program that was funded by Ted Geisel, Dr. Seuss. Then I taught junior high in a ghetto district. And I taught juvenile delinquents for the California Youth Authority. I taught adult school and community college prior to teaching at the University of California, San Diego. Then I was asked to teach at CalArts. In the mid-1980s, I got a Guggenheim grant and left for a while. I started to miss teaching, so I called up friends at the University of California, Los Angeles and said, “I’ll teach half time.” They said, “Fine.” And I quit working there about four years ago.

John Baldessari, Hanging Man (With Sunglasses), 1984. Black-and-white photographs; 61 1/2 × 47 1/2 inches. © John Baldessari. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

Art21: Obviously you love teaching. Tell me why you love it so much?

Baldessari: I got my degree in art and my sister said, “How are you going to support yourself?” So I got a teaching credential. I get bored easily and I thought how could I make this not boring? I decided to approach it like art and that of course means invention. Teaching at CalArts was really helpful because we had no grades, no curriculum. Students came to your class because they wanted to; there was no reason they had to. We actually let some instructors go because they didn’t have any students. So you had to be inventive.

You try to think of ways to make your time in the classroom like you’re making art in some way. A vital lesson for me was learning that teaching is about communication. Lecturing doesn’t do it. You have to see the light in the student’s eyes; you have to see that they get it. And if you don’t see the light, then you try another approach and then another approach. I realized that that attitude was filtering into my art—that you have to communicate. Teaching and art began to cross-pollinate and one affected the other. I realized that art was about communication. I was learning how to communicate by teaching. In effect I was saying, the art I do is what I’m talking about in the classroom and vice versa and they’re interchangeable.

I think I wanted to be a social worker. My father was Catholic and my mother was Lutheran. We went to a local Methodist church and I certainly got a love of literature reading the King James Version of the Bible. I got a real sense of moral obligation and I think that’s why I was a late starter in art because art didn’t seem to do anybody any good that I could see. It didn’t heal bones; it didn’t help people find shelter. Teaching juvenile delinquents was a real eye-opener for me, because they had a stronger need for art than I did. And they were criminals. We had no other shared values, but they cared more about art then I did. It dawned on me that it must provide some sort of spiritual nourishment—as terrible as that sounds—but it must.